The diesel-punk world of Broken Gargoyles is set in 1925 in an alternative post-war US, where much has been lost and is yet to be rebuilt. It features robots (so far only ‘promo’ bots), peculiar vehicles, architecture with a slightly futuristic spin on Art Deco, as well as imagery familiar from the roaring twenties.

The name of the novel itself is a term coined after WWI as a way to refer to the disfigured veterans, and it’s these the story is centred around: the struggle of war heroes severely scarred by the inhumane brutality of the battlefield. The narrative explores the disillusionment of our ‘broken gargoyles’ who carry the evidence of their sacrifice on their faces. Their human drama is downsized to horror entertainment or mere statistics by a society that glorifies military achievements and is quick to adjust to the safety and freedom which come at the expense of others, but refuses to acknowledge the unsightly reality of war. Those ‘others’ are left alone to deal with the destructive impact the events on the battlefield have had on them, discarded once they have served their purpose and unable to get on with their lives like everyone else around appears to be doing.

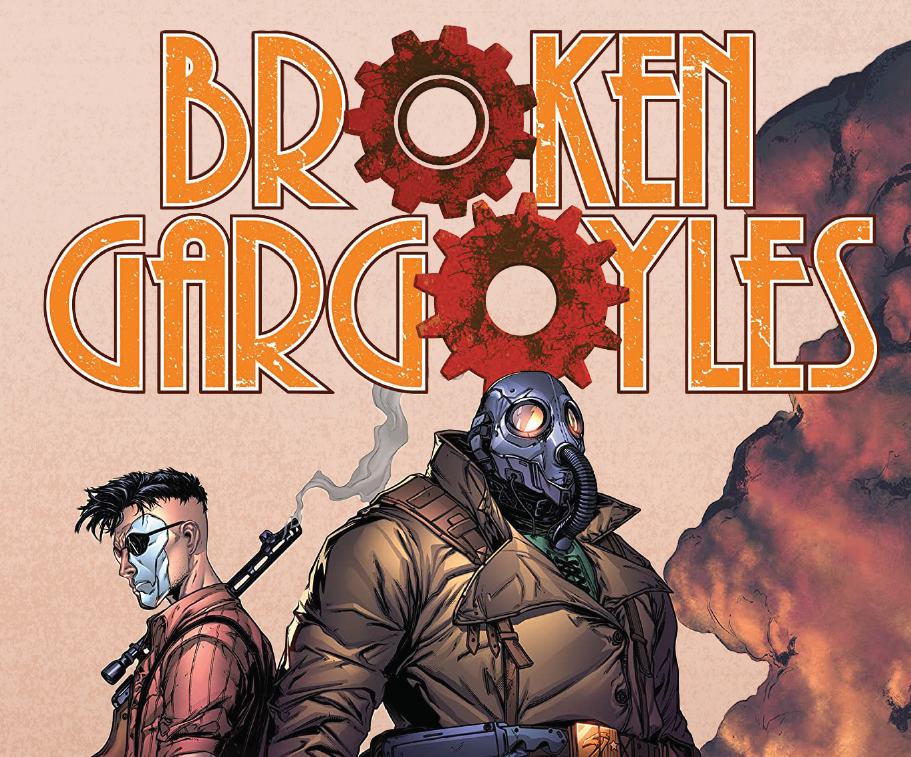

We are introduced to two main characters, and by the end of the first book it becomes clear that they have history together and that the rising conflict between them is going to be one of the main pillars of the plot in subsequent novels. As the book opens, we witness William being left by his wife and child in a church in New York. He is depressed, cannot keep a job, and seeks solace in the bottom of the bottle. Half his face is covered with a metal mask and we find out from a brief exchange between him and his son that his missing eye is the reason for his unemployment.

At the other end of the country, in the Arizona desert, main character number two enters the story with a rocket launcher and a “KABOOM!” Commander Douglas Prescott is a determined soldier on a mission, and doesn’t let anything stand in his way. He is covered up by heavy clothing and a gas mask and utilises his striking look as an effective means of intimidation. Already we see that the narrative is built upon a duality that sets apart the two characters. While William seems to have lost his will and sense of purpose, Douglas epitomises those two features and supports them with radical action. To add to this contrast, the environments where those two are set also differ greatly: Arizona is a vast, flat desert where one could peer into the endless dusty horizon to find nothing to stop their gaze upon; while New York has its massive vertical constructions, noise and crowds. Very different, yet very similar in the sense that both are arguably scarred by desolation and decay: just like William and Doug.

“Writing a story about veterans coming home from war by someone who didn’t serve was something I was cautious with.”

Bob Salley

Although both main characters wear masks, the way their visual identities are built is very far from the masking approach to character creation that is popular in comics. Both of them have strong, memorable, recognisable features which perpetuate their otherness. They simply could not blend in anywhere, unless they were surrounded by other ‘broken gargoyles’. They are not meant to resemble the reader. We, the readers, could empathise and perhaps relate in some way, but not to an extent where we align with those characters and find a reflection of ourselves within them. We are to accept that we belong to the society that has manufactured those broken lives, and is subject to criticism in this book.

Every element of this piece compliments and builds upon the rest in a way that makes you wonder how long the creative team must have spent in discussions. Writer Bob Salley, with years of experience in graphic novel scripting across various genres, weaves a gripping plot with a dialogue rich in wit, historic references and symbolism. All of this, combined with the visual splendour of Stan Yak’s art, makes for a powerful read that’s very hard to put down.

I went through this book a few times just to take in more of the fantastic imagery. The facial expressions are done very well and successfully convey different emotions. The action sequences are dynamic and thrilling. All of the different angles and approaches to composition lead the gaze where it should be focused, and help to give a good feel for the atmosphere of the environment where the action takes place by showing the reader each scene in its entirety. I enjoyed the texturised ruggedness of the main characters that makes them stand out from everyone and everything else even more.

While William seems to have lost his will and sense of purpose, Douglas epitomises those two features.

Robert Nugent and Marco Pagnotta have done wonders with the colours and textures, which also fit the theme perfectly well with their subdued, warm, vintage look, and I am in love with the portrayal of light. The letters by Justin Birch are a perfect example of the memorable stylistic choices in Broken Gargoyles with their successful visual representation of sound. I really liked that the speech bubbles of one of the characters are coloured in red and shaped like what appears to be gears; this is a constant reminder that the character’s voice is unusual and probably unsettling.

One of my favourite moments of social commentary sees William walking through the streets of New York and stopping in front of a poster featuring an image of a soldier, with the slogan: “After the welcome home — a job!” The romanticised image of the veteran, fabricated by people that have not seen the battlefield, and the unsightly reality of war whom those same people can’t stand to look at stand face to face in a poetically ironic scene amidst a decaying city.

Acceptance of reality is an issue not only when it comes to society reluctantly welcoming back its scarred and traumatised soldiers, but also the other way around. Soldiers may have physically moved from one place to another, but mentally they are stuck in the trenches while everything and everyone around them is changing rapidly. This theme was brought up via a parallel between William’s wandering around New York and Doug’s unnamed fellow soldiers sitting atop a cliff with a prisoner they had just liberated by chance, watching the sun set over the desert. “I like to move stones. When you’re trapped somewhere with no hopes to ever leave…feels good to set something free,” says the prisoner, while throwing a stone over the edge of the cliff. The other two begin doing the same in a ritualistic manner. This gesture opens the conversation about the veterans’ silent suffering in a time when it was believed that ‘real men don’t cry’, and gives us a glimpse into their damaged and chaotic internal world.

*

I spoke to writer Bob Salley about Broken Gargoyles.

In the past you’ve tackled science fiction in Salvagers, fantasy in Ogre and Ogres, and humour in Jasper’s Starlight Tavern. What inspired you to delve into the human world and why did you pick specifically the period after WWI as a focal point? Why now?

I was writing a post-Civil War western when I came across the term ‘Broken Gargoyles’, and it intrigued me enough to dive into days of reading up not only on the men who came back from war facially disfigured, but also post-WWI America as a whole. It was not a good time for most people and the further down the rabbit-hole I went, the more and more it seemed like a dystopian time for our country.

How long did it take to bring Broken Gargoyles from an idea to a finished first book?

I believe it took almost a year. It wasn’t something I wanted to rush. As I said, there was a lot of research involved as I developed the outline. I hired an editor (Drena Jo) to make sure I did this the right way.

Did you purposefully time the initial release for 2020, the roaring twenties of this century?

Hahaha… I wish I could say “Yes” but I’m just not that clever.

Are there elements of the story that have been drastically altered since the initial conception? Have you had to make any compromises?

No… Not really. Writing a story about veterans coming home from war by someone who didn’t serve was something I was cautious with. I had several vets read the script and for the most part I got back extremely positive feedback.

You’ve painted Doug as a notorious and rather magnetic antihero. What were the influences that resulted in the birth of this character?

William Foster (Falling Down starring Michael Douglas) and Walter White (Breaking Bad). Those were men who had enough of being pushed around.

What challenges do you face during the creative process?

Deadlines.

Has the lockdown affected your team’s work on the next volumes in any way?

I think it affected me, most. I had a hard time getting my motivation when everything closed and we were in quarantine. I thought it would give me more time to write, but I just couldn’t find the motivation.

When should we expect the release of the second book?

Issue One is hitting shelves August 26th and Issue 2 will be out at the end of September.

Thanks for your time!

*

I very much enjoyed the first book and I’m looking forward to seeing what happens next. How did Doug come back from the dead and what’s his plan? Will we ever get to see his face? What exactly happened between Doug and William? What more will happen between them? Who are Doug’s unnamed counterparts and is the prisoner now part of the team? Will they all find redemption or is that a lost cause?

Broken Gargoyles is published by Source Point Press.