From the Parallel Worlds Magazine archive.

I’ll start by saying that I absolutely expected to dislike The King’s Dilemma. There are a few genres of game I really struggle to enjoy: social deduction games, for example, such as Coup, Werewolf, or Spyfall. I’m also not particularly into games which revolve around either bluffing or bidding. Perhaps it’s because I enjoy the feeling of mindful puzzle-solving when I sit down to a board game, rather than being expected to give a performance.

As such, I was particularly intrigued to find that I loved The King’s Dilemma. I could probably even cut to the chase and declare this as one of the most remarkable games I’ve played in a while; which is very odd, considering its gameplay can be best summed up as… all of the above.

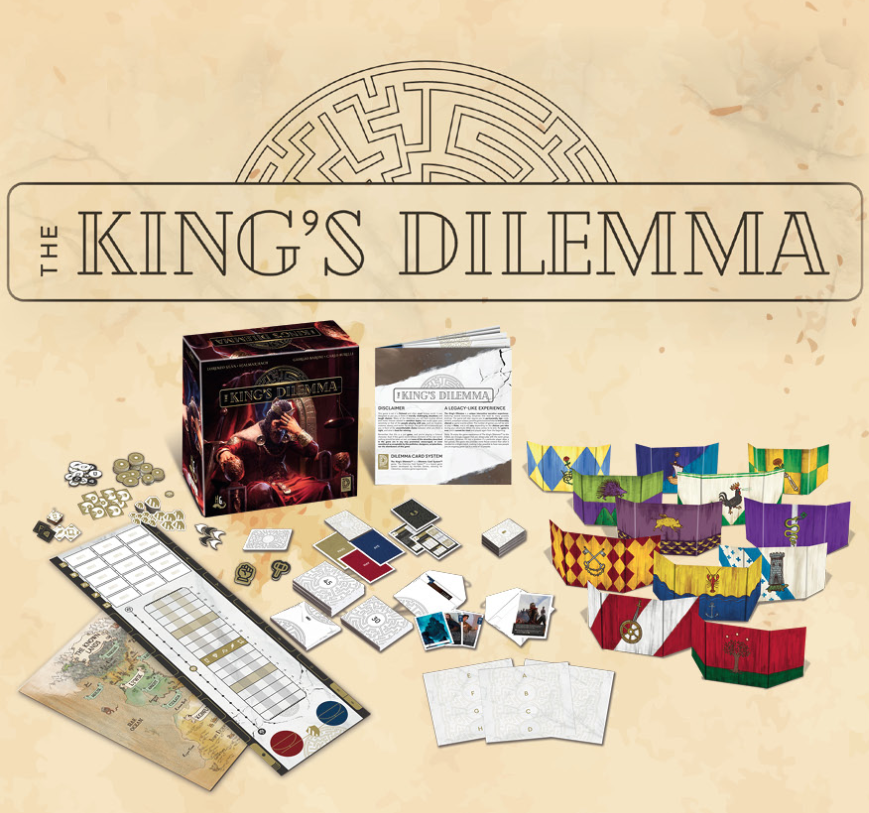

For the setting, imagine a Game of Thrones-style political landscape of intrigue and private agendas. In The King’s Dilemma, each game revolves around the reign of a King and ends when the King either dies or is forced to abdicate by national instability. The players assume the role of the representative of a noble house, each with their own backstory, to vie for influence in the court. The houses are a typically feudal mix of unsavoury militants, bastards, would-be quislings and capitalists. The game is played through a series of rounds, in which a ‘dilemma’ is drawn which requires a binary Aye or Nay vote in the parliament. To manipulate the outcome, players can bribe each other, make alliances, convince each other with rhetoric and even tactically abstain in order to influence which laws get passed and which do not. Players spend influence tokens to bolster the strength of their vote and can pay Coin to encourage other players to vote their way.

What’s initially clever about The King’s Dilemma is that each player has their own hidden set of criteria which determines how they want the kingdom to perform.

The laws passed affect the Security, Wealth, Morale, Knowledge and Food of the Kingdom, which move up and down in a positive/negative scale as they are affected by the ruling. For example, a decision whether to investigate irregularities at the local convent may potentially increase security, but decrease national morale. Alongside these is the Stability marker, representing the King. With every move of one of the other tokens, the stability marker makes a matching move. Too much in any direction, the King will be forced to abdicate — the Kingdom is only ‘stable’ while the overall balance is kept.

However, voting on these dilemmas is not without consequence. As well as affecting the Kingdom’s fortunes, many choices result in additional dilemmas being revealed from a secret envelope and added to your deck of possible future events. There’s a story which plays out as more dilemmas are revealed. This is why I’m shying away from giving too many examples in this review: it would be a huge spoiler if I did, and seeing the unintended consequences of your choices is extremely satisfying.

What emerges from this mix is a gripping, story-driven game of political intrigue.

What’s initially clever about The King’s Dilemma is that each player has their own hidden set of criteria which determines how they want the kingdom to perform. Getting points is not necessarily in line with prosperity for the nation. Additionally, everybody is playing to a different objective: you may be playing as the Moderate, who scores points for each of the five measures which remain in the middle area of the track. You may be the Extremist role, which rewards points for the distance between the highest positive track and the lowest negative track. You may be Greedy, who scores for ensuring that only a couple of select parts of the kingdom either prosper or fail. I had a lot of fun with the Greedy role, as this role scores big for having the most gold coins at the end of the game. I simply made it very clear that if other parties wanted my vote to go their way, I was amenable to contributions.

What emerges from this mix is a gripping, story-driven game of political intrigue. The politics isn’t forced, it grows naturally from the setting. As a player, your main concern is the movement of little sliders on the agenda board; but when this is combined with morally ambiguous events, even the least-inclined roleplayer in the room will find themselves embodying the demands of their ‘house’. The only way to get the outcome you need is to manipulate the play of votes around the table: from subtle inceptions with your fellow players, to carefully managing the collection of influence tokens at your disposal.

Seeing the unintended consequences of your choices is extremely satisfying.

And those ballots matter so much, because this is a Legacy game (where components can be changed through play) and when a vote is passed, the player with the most influence behind the ballot signs their name to the card. The importance of this won’t be apparent in your first game. It’s only when you play your second session, and your starting influence is reduced for every ‘bad’ event with your name on it, that you start to realise that it’s not just about winning ballots — but also about getting some other sucker to put their names to the bad ones.

And that’s really the key thing about The King’s Dilemma. You’ll get little out of it if you play it once. You need to play it again and again with the same group of players, seeing the web spread out from the decisions your table allows to pass; whether through cynicism, ambition, or a simple lack of power and timing at the point of each ballot.

While that’s wonderful and truly epic, it’s also the hardest thing to recommend about this game. I’ve played it at its maximum of five players, and it really sings. The nuance, conflicting goals and natural politics which arises from each dilemma is wonderful and I suspect would be sorely lacking at lower player counts. But, if you’re any kind of gamer, you’ll know that the larger the group, the harder it is to maintain commitment and scheduling over a campaign — especially in these crazy days.

Maybe that’s the point, and once this is all over there will be a hunger for regular, well-attended game nights again. If that does happen, see your way past the deluge of large campaign games now on the market and make sure The King’s Dilemma is at the top of your list.